Executive Summary

The COP29 climate change conference falls at a critical time, as countries evaluate their pledges to climate action before submitting revised ambitions in respective Nationally Determined Contributions — or NDCs — next year. Stimulating collective ambition requires leadership, precisely what COP29 host Azerbaijan has yet to deliver in its own plans. The host nation's approach is modest, at best, with wind and solar projects in development only expected to bring about a 10% increase in renewables share of capacity by 2027 and no plans for further projects beyond that date. Global Energy Monitor's Global Integrated Power Tracker data indicate similarly low levels of progress against unambitious targets across the region, with a 13 GW deficit in targeted renewable capacity additions among Caucasus and Central Asia (CCA) countries. At the same time, the fossil-powered buildout continues apace, with more than three times as much fossil capacity under construction in the CCA region than from wind and utility-scale solar. Course correction is essential to uphold the collective pledges on energy made at COP28.

Key Findings

- Power projects in development fall short of meeting the renewable energy targets of countries in the Caucasus and Central Asia (CCA) region. Six CCA countries detail targets in the 2030–2040 range for renewable capacity additions — including wind, solar, and hydropower — adding up to 43 GW (Turkmenistan and Kyrgyzstan lack specific targets). However, GEM data show 30 GW of renewable capacity in development across these same six CCA countries, a 13 GW deficit. Georgia and Tajikistan’s targets rely on large hydropower projects, which, aside from associated environmental and financial sustainability concerns, may offer a limited contribution in the 2030 time frame due to long construction lead times.

- COP29 host Azerbaijan shows no in-development wind or utility-scale solar projects beyond those due for completion by 2027, implying capacity additions are just sufficient for achieving the country's stated target of a 30% renewable share of capacity by 2030 — roughly a 2 GW addition. Recent announcements from the Azeri Government suggest a rollout of wind and solar capacity by 2030 of up to 8 GW. However, the lack of further renewables projects in the project pipeline calls into question the integrity of the energy transition in Azerbaijan. Furthermore, the 30% target, first announced five years ago, only represents a ~10% increase over legacy hydropower capacity, and suggests limited ambition in the current renewables target.

- All eight countries in the CCA region are developing additional coal or oil and gas plant capacity. Oil and gas plant capacity leads the buildout, with 24 GW of capacity in development, half of which is under construction. By comparison, new coal plant capacity is getting built at a far lesser rate, with only two small coal units currently under construction in Kazakhstan, due to replace existing units up for retirement. However, the risk of further coal plant expansion remains, with nearly 8 GW capacity in development across four CCA countries.

- More than three times as much fossil capacity is under construction in the CCA region than from wind and utility-scale solar. Total capacity under construction from wind and utility-scale solar in CCA countries totals 3.5 GW, less than a third of the figure for projects fueled by coal, oil, or gas. An additional 4.8 GW of hydropower capacity is also under construction but mostly comprises two large projects that won’t contribute to power generation before 2030.

Introduction

After back-to-back gatherings in the Middle East, the annual United Nations Climate Change Conference or Conference of the Parties (COP) moves to Baku, Azerbaijan, marking the first time the event has been hosted by a country in the Caucasus and Central Asia (CCA) region.

The Azerbaijani presidency faces the tall task of building on the achievements of COP28, namely the “UAE Consensus” that calls on countries to transition away from fossil fuels. Chief amongst a long list of priorities are agreeing on a new post-2025 finance goal, developing ambitious updated Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), and operationalizing the provisions of the Global Goal on Adaptation and carbon markets under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement.

However, Azerbaijan’s hosting of COP29 has attracted criticism, increasingly referred to as an authoritarian petrostate, with concerns over the strength and integrity of the country’s role in shaping and progressing the conference agenda. Any mention of transitioning away from fossil fuels was absent in President-Designate Mukhtar Babayev’s “action agenda” of priority initiatives to be brought to the table in Baku in November, and an independent assessment has found the country’s climate actions “critically insufficient.” The country’s active development of new oil and gas fields and allegations of a renewed crackdown on media and civil society activism add to the concerns over the host’s legitimacy.

However, Azerbaijan is not the first and won't be the last fossil fuel-producing country to take center stage in climate diplomacy. The door has not yet closed on the COP29 host to demonstrate climate leadership, with one of its strongest available actions to submit an early and ambitious updated NDC. Such “bar-raising” actions could help push other countries into higher levels of commitment, particularly amongst neighboring countries where fossil fuel extraction is still a cornerstone industry. As a powerful platform to promote a regional focus and encourage involvement and support, Azerbaijan's COP29 presidency can raise international awareness for the Central Asia and Caucasus region and its possibilities for a clean energy transition.

Spanning three countries in the South Caucasus — Azerbaijan, Armenia, Georgia — and five countries in Central Asia — Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and the Kyrgyz Republic (Kyrgyzstan hereafter) — the CCA region's national governments have made strides in recent years with the introduction of carbon neutrality plans, and the geography harbors significant potential for solar, wind, and hydropower. Yet, investments still favor development plans for coal and oil and gas, and the challenges to energy transition in the region are manifest: aging Soviet-era transmission infrastructure, winter energy crises, energy security concerns, regional trade constraints, and a lack of domestic financial resources for investment.

As global attention turns to this year's marquee climate change event, this report seeks to interrogate the status of power sector transition in the CCA region and highlight the distance still to go in phasing out fossil fuels. The report's analysis draws upon GEM's trackers for coal, gas, oil, hydropower, utility-scale solar, wind, nuclear, bioenergy, and geothermal, housed within the Global Integrated Power Tracker (GIPT). For a detailed analysis of each CCA country, see the dedicated country profile sections (Azerbaijan, Armenia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Kyrgyzstan) in the downloadable PDF version of the report. See dedicated summary tables for summaries of GEM's power sector data for CCA countries.

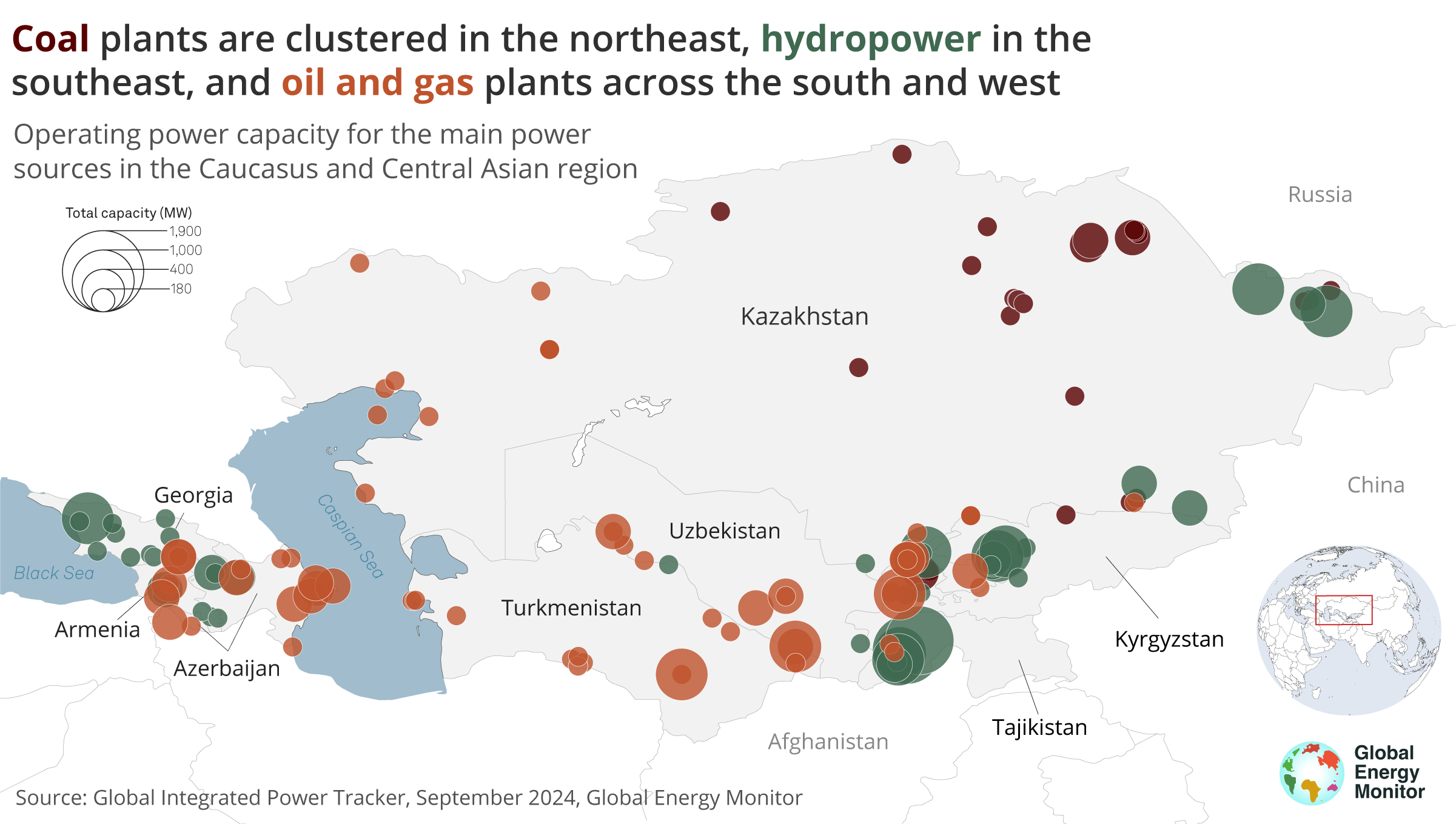

I. The CCA power sector is largely old and fossil-fueled, with underutilized wind and solar potential

The power sector development in CCA countries reflects the region’s endowments of coal, oil, gas, and hydropower resources. The region’s operating oil and gas plants tend towards the south and west of the CCA region, concentrating around major gas fields in Uzbekistan (Kashkadarya and Fergana Valley), Turkmenistan (Amu Darya basin), and Azerbaijan (Shah Deniz and Umid). Oil and gas plants constitute the majority of total power capacity in Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan, and Armenia.

Four CCA countries operate coal plants, but only Kazakhstan relies heavily on this source, which makes up around 57% of the country’s total operating capacity and 80% of the region’s total operating coal capacity. Operating coal plants co-locate with major coal mines towards the northeast, particularly in the Palovdar region, host to the Ekibastuz coal basin and Kazakhstan’s largest coal mine, Bogatyr.

Three CCA countries have a majority share of hydropower in their respective power mixes, and all but Turkmenistan have operating hydropower facilities. These hydropower facilities cluster towards the mountainous south and east, particularly in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, where hydropower is the primary power source. The Caucasus mountains also host numerous hydropower facilities, which Georgia relies on most heavily, accounting for nearly three-quarters of its power mix.

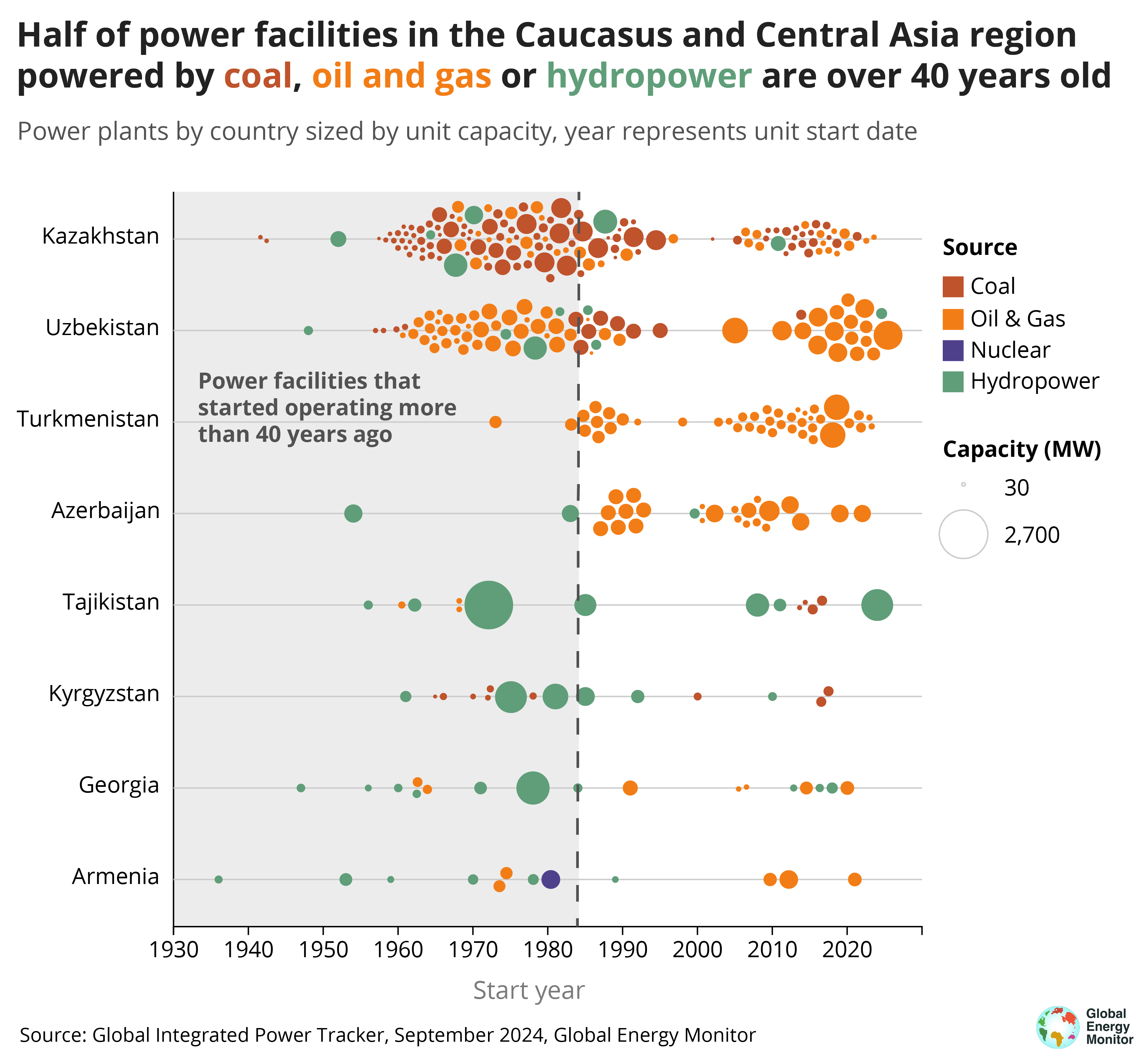

Operating power facilities across the CCA region are relatively old, with GEM data showing an average age amongst coal, gas, and hydropower plants of 40 years, double the global average. Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan have comparatively younger power plants. Still, upgrades were required at the countries' oldest and largest power plants, the Azerbaijan thermal power plant and the Mary power station. In addition to lower efficiency, older power sector assets are prone to equipment failure, prompting increased supply interruptions and accidents in recent years. As many thermal power plants in the eastern CCA countries are combined heat and power plants (CHPs), which also provide heating to the residential sector, plant failures leave some residents without heat during the region's harsh winters. Furthermore, the region's power grid faces a similar situation and suffers above-average network losses from worn-out or poorly maintained infrastructure.

The region's predominantly state-owned national energy companies often lack incentives for investments, and regulated energy tariffs typically don't reflect the cost of production, further indebting producers. Increasing power demand across the region, averaging 3% per annum over the last decade, compounds the issues faced by the underperforming power system. Despite many CCA countries' positions as major fossil energy producers, several have resorted to electricity imports in recent years to cover deficits, particularly in winter. A similar situation also occurs in the hydropower-dominated power systems of the CCA region, where aging infrastructure contends with seasonal water shortages and climate-affected water availability.

Despite the numerous challenges facing power sector development amongst CCA countries, the region also holds great potential for cleaner forms of electricity generation. Notably, the technical potential for wind and solar power is vast within the region, particularly in the lowlands and plains of Central Asia. This potential is not only constrained to the region’s largest countries. Azerbaijan has a technical potential for 157 GW of offshore wind and 23 GW of solar capacity.

Additionally, several power sector developments point toward a nascent movement for energy sector transition in the region. For instance, Kazakhstan pioneered renewables targets with accompanying support mechanisms amongst CCA countries, evolving to a competitive process in subsequent years that saw the first online auction for renewables projects in 2018. The country currently hosts more than double the combined operating wind and solar capacity of all other CCA countries. Uzbekistan is following suit, introducing competitive bidding processes to attract foreign investment in large-scale solar projects, and was the leading recipient in the region four years in a row for funding from the European Bank of Reconstruction and Development. Furthermore, several initiatives target enhanced regional electricity integration, notably efforts for Tajikistan and Turkmenistan to reconnect their national power systems to the Central Asian Power System (CAPS).

Despite these steps in the right direction and the great potential of wind and solar power in the region, fossil capacity additions remain the mainstay of power system development amongst CCA countries.

II. All CCA countries have fossil-fueled power capacity in development

All eight countries in the CCA region have either coal or oil or gas plants at one of three “in development” stages tracked by GEM data — projects that have been “announced” or are in the “pre-construction” and “construction” phases. In-development oil and gas plants are more prevalent than coal, with all but Tajikistan currently considering new oil and gas capacity. Four CCA countries are planning new coal capacity, but only Kazakhstan has new units under construction.

With 24 GW capacity in development, oil and gas outnumbers the same figure for coal (7.9 GW) by three to one. Nearly half of the total figure for in-development oil and gas capacity is made up of projects under construction (11.8 GW). This contrasts with in-development coal projects, where just two new units, totaling 195 MW, are under construction, according to GEM data.

Although most CCA countries are pursuing new oil and gas plants, only Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan have oil and gas capacity under construction. Already the most gas-heavy countries in the region, the proposed oil and gas plants will radically augment existing capacity if built. For instance, in-development plants in Kazakhstan would triple existing operational oil and gas capacity. In Uzbekistan, if 10 GW of in-development oil and gas capacity is built, the country’s operating oil and gas plant fleet would reach 24 GW, double the figure for any other CCA country.

Outside of these four countries, oil and gas projects in development also have the potential to significantly expand capacity in less gas-heavy power mixes. For example, in Georgia, the planned expansion of the Gardabani Combined Cycle power station would increase the current gas plant fleet by more than half. Kyrgyzstan currently has no operating oil or gas plant capacity but is actively pursuing over 1,600 MW of new oil and gas capacity over three separate project locations, equivalent to 40% of the total power capacity in the country.According to GEM data, planned retirements of currently operating oil and gas plants are limited. Only three oil and gas units detail potential plans for decommissioning: a 60 MW unit at the Atyrau CHP power station in Kazakhstan and two 300 MW units at the Syrdarya power station in Uzbekistan, all in 2024. Thus, net oil and gas capacity additions in the CCA region prevail. GEM data show over 70% of in-development oil and gas capacity in the CCA region slated for operation by 2027. If built, the oil and gas capacity coming online by that year would constitute a 50% increase in the existing operating capacity of oil and gas plants in the CCA region.

Four CCA countries are planning new coal projects, totalling 7.9 GW of capacity in development. However, GEM data show a far smaller proportion of this in-development coal figure in the construction phase compared to oil and gas plants, some 195 MW, or less than 3%. The under-construction coal capacity will replace two existing units at coal plants in Kazakhstan, a 130 MW unit at the Karaganda State Regional power station-2, and a 65 MW unit at the Ust-Kamenogorsk TETS power station. Kazakhstan also leads the CCA region for pre-construction and announced coal projects, totalling 4.6 GW, with over half the proposed capacity located in Ekibastuz, a major coal mining center in northeastern Kazakhstan.

Outside of Kazakhstan, the new coal capacity in Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan comprises announced projects only, totalling 3 GW. Kyrgyzstan accounts for 1,860 MW of this announced capacity across two projects: the 660 MW Jalal-Abad power station, with Russian contractor AB Energo as the proposed contractor, and the 600 MW Kara-Keche power station, for which the Kyrgyz Ministry of Energy and China National Electric Engineering have a memorandum on construction. The future of announced coal plants in Tajikistan and Uzbekistan appears less assured. If built, the Fon-Yagnob power station would more than double Tajikistan’s operating coal fleet. However, the current development status of the project remains unknown. And while the announced 300-600 MW expansion at the Angren power station in Uzbekistan appeared to have attracted China Railway and PowerChina as investment partners, development updates were not forthcoming in 2024.

As well as new coal capacity in development, GEM data show 1,686 MW of operating coal-fired capacity in the CCA region with a planned retirement date. Most of this capacity is due to come offline by 2027 and is associated with units at four plants: three in Kazakhstan (two at Almaty, plus the Zhezkazgan power station), and the Bishkek power station in Kyrgyzstan. Depending on whether in-development coal projects are realized, these planned retirements could see a net reduction in the total CCA operating coal fleet in the coming years. However, most coal units scheduled for retirement at these three plants are designated for conversion to gas-firing or replacement with gas plant technologies of equal or greater capacity.

III. Non fossil-fueled capacity in development is 50% greater than the figure for coal and oil and gas projects but is being built at half the rate

Looking beyond prospective coal and oil and gas projects, capacity in development across CCA countries appears to favor non-fossil sources. GEM data show in-development wind, utility-scale solar, nuclear, and hydropower projects in the CCA region totalling 48.3 GW capacity, about 50% greater than the equivalent figure for coal and oil and gas projects (31.9 GW).

However, only 17% of non-fossil power projects are in the construction phase compared to 34% for coal and oil and gas projects. Furthermore, over half of the 8 GW non-fossil capacity in construction is accounted for by two large hydropower projects — the Rogun plant in Tajikistan and the Kambarata-1 plant in Kyrgyzstan. Two of the Rogun hydroelectric plant’s six 600 MW units are now operational, but full commissioning is not expected until 2033. At the 1,860 MW Kambarata-1 plant, construction of the power facility itself won’t commence until 2025, with full commissioning a further nine years off. Although the two projects are major components of a drive to increase generation and improve domestic and regional energy security, long construction times won’t see their contribution before 2030. Furthermore, the projects face the added challenge of managing the region’s shared water resources, which sees upstream Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan replenish reservoirs in summer while downstream Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan depend on that same water during the main growing season.

GEM data show Armenia, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan with plans for new nuclear power facilities. Still, the majority of this new capacity is at the announced stage. The Armenian government is considering plans for additional nuclear capacity and is reviewing options for a 1,200 MW plant and smaller modular units but has yet to identify a favored supplier. On October 6, 2024, Kazakhstan conducted a national referendum on the proposed 2.4 GW Ulken nuclear power plant, with 71% of those who cast ballots voting in favor, despite public opposition, reported irregularities at the polls, and silencing critics and activists. Announced plans for the 2.4 GW Navoi nuclear power plant in Uzbekistan appear to have halted. Instead, a new 330 MW six-unit small modular reactor (SMR) nuclear power plant is in development in the Jizzakh region of Uzbekistan, with a targeted commissioning year of 2028. However, the Uzbek Energy Minister commented in a recent interview that the new nuclear plant is still at the design phase. So, as with hydropower projects, new nuclear plants are, at best, medium-to-long-term options for increasing generation.

Beyond these long lead-time hydropower and nuclear projects, construction phase projects for non-fossil power sources are extremely limited in the CCA region. GEM data show Uzbekistan making up virtually all wind and utility-scale solar projects under construction in the CCA region (a single project in Armenia — the 55 MW Masrik solar farm — is the only other). Under construction wind and solar capacity in Uzbekistan comprises two large 500 MW wind farms and nine solar farms, averaging 270 MW, totaling 2,447 MW. However, this is still less than the 5,848 MW oil and gas capacity under construction in the country (even when taking into account 600 MW due for decommissioning at the Syrdarya power station).

Capacity additions from small-scale facilities below the threshold GEM data covers could make important non-fossil contributions to the power mix in the CCA region. However, per-country research (see country profile sections below) suggests this small-scale segment has yet to make significant inroads in most CCA countries. For example, most CCA countries with hydropower resources are planning small-scale hydropower facilities. Yet, these additions are generally piecemeal and won't offer sufficient capacity to supplant dominant power sources. Planned small-scale hydropower additions of significant size were only identified for Uzbekistan (438 MW) and Armenia (380 MW).

The situation is comparable for distributed solar, where stated plans and support measures are rarely detailed and appear to be a missed opportunity amongst the CAA countries. However, the region holds examples of successful scale-up of distributed solar PV, again from Uzbekistan and Armenia. With support from a feed-in tariff, 35,000 residential households in Uzbekistan currently host 150 MW rooftop solar PV. In Armenia, distributed solar PV capacity stood at 354 MW as of September 2024, up from 18 MW five years previously, providing 9% of national electricity generation in H1 2024.

Despite these examples of a distributed approach, wind and solar capacity in development across the CCA region generally favors larger, utility-scale projects. GEM data show that the majority of these in-development wind and solar projects are implemented or owned by firms based in the Middle East or China, notably the Saudi firm ACWA Power, Masdar of the United Arab Emirates, and several Chinese utility companies (e.g., China Gezhouba Group Co.). It will be important to monitor the development of this ownership pattern for new wind and solar capacity in the CCA region, to ensure the scalability and long-term financial sustainability of the capacity additions.

Owner-operators based in the Middle East and China account for 80% of wind and utility-scale solar capacity in development in the CCA region

IV. Wind, utility-scale solar, and hydropower capacity in development falls short of renewable energy targets in most CCA countries

All CCA countries have submitted updates to their first nationally determined contributions (NDCs) under the Paris Agreement, pledging varying degrees of climate actions contingent on the level of international support received. CCA countries have also adopted various energy strategies aligned with their international climate commitments, typically framed within respective national development plans (see accompanying GEM Wiki page for a compilation of climate pledges and energy sector targets).

Comparing GIPT tracker data for power projects in development with capacity targets detailed within these energy strategies reveals the distance between ambition and reality. Six CCA countries detail targets for renewable capacity additions in the 2030–2040 range — including wind, solar and hydropower — adding up to 43 GW (Turkmenistan and Kyrgyzstan lack specific renewables targets). However, GEM power tracker data show 30 GW renewable capacity in development across these same six CCA countries, a 13 GW deficit. An assessment of each CCA country shows some cases where capacity in development exceeds stated renewable targets. Yet, these cases are due to reliance on large hydropower projects or due to unambitious targets.

Azerbaijan appears to be an example of the latter. The COP29 host has been keen to highlight how plans for 2 GW of additional renewables capacity will see the country exceed a 30% renewable share of total electricity capacity by 2030. GEM data suggest wind and utility-scale solar PV projects coming online by 2027 will fulfill nearly all of the 2 GW quota. Around 1,000 MW comes from projects implemented by Abu Dhabi Future Energy Company (better known as Masdar), in collaboration with SOCAR, the State Oil Company of Azerbaijan, including the Bilasuvar (445 MW) and Neftchala (315 MW) solar plants, as well as the Absheron-Garadagh wind farm (240 MW). Saudi energy group ACWA leads the Area 1 / Khizi 3 wind farm (240 MW), with an additional 200 MW wind project in discussion, while three additional solar projects account for a further 440 MW.

However, GEM data show no further renewable projects in development in Azerbaijan, calling into question the certainty of capacity increase beyond the 2 GW additions. Recent public statements by the Energy Ministry have indicated plans to commission 7 to 8 GW of additional renewable capacity by 2030, with a pipeline of candidate renewable projects totalling 28 GW. Although the 2 GW of wind and solar additions in development mark a significant increase from a low base, the actual generation that the new farms produce would be unlikely to match that of new gas capacity under construction, specifically, the 1,280 MW Mingecevir gas power station, due for commissioning by the end of 2024.

Neighboring countries of Armenia and Georgia both target high renewable shares in electricity generation: Georgia 85% by 2030 and Armenia 50% by 2040, helped by existing large hydropower facilities. However, GEM data suggest renewables projects in development in Armenia falling short of the targeted capacity increases, particularly for wind, with no known projects tracked. Compared to stated targets, the apparent excess of renewable capacity in Georgia is due to nearly 2 GW of hydropower projects in development. Aside from the long construction lead times of large hydropower projects, several of the proposed projects face public opposition due to associated environmental and social disruption, notably the 700 MW Khudoni Hydro Power Plant. GEM data for in-development wind and utility-scale solar in Georgia total only one-third of the targeted increase.

A similar diagnosis can be made for hydropower-dominated Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, where total capacity in development favors new hydropower. The available information on in-development hydropower in Tajikistan does not indicate how many of these projects would become operational in time to contribute to the country’s target of 1,500 MW renewable addition by 2030. Kyrgyzstan’s National Development Strategy from 2018 references a 10% share in the total energy mix from renewables (excluding large hydropower) but lacks any indication of the breakdown between sources or the necessary capacity additions. However, GEM data suggest that Kyrgyzstan has the most renewable capacity in development as a proportion of operating capacity. Although three-quarters of this 9,700 MW in-development total is for hydropower projects, the 2,480 MW of wind and utility-solar projects would constitute a substantial addition if built.

Despite Kazakhstan's pipeline of coal and oil and gas projects (the largest in the CCA region), a presidential decree issued in June 2024 includes targets for increasing the non-fossil share of electricity generation to 15% by 2030, rising to 50% by 2050. The Government's Power Sector Development Plan to 2035, from earlier in the year, includes targets of 9,000 MW wind, 500 MW solar, and 2,660 MW hydropower. However, GEM data from power projects in development are well below these figures, with no renewables projects in the construction phase.

In early 2024, the Senate of Uzbekistan voted to increase renewable energy targets to 27 GW by 2030 and the share of renewable power generation to 40% (including hydropower). GEM data show that Uzbekistan has the largest absolute volume of renewable capacity in development in the CCA region and the most capacity under construction. However, the total figure for wind, utility-scale solar, and hydropower projects in development still falls 30% short of the target, at 19.2 GW.

Turkmenistan’s NDC details one of the least ambitious targets in the CCA region, and its reference to an intensity-based target is unlikely to bring about absolute reductions in emissions. Neither the Turkmen NDC nor the National Strategy of Turkmenistan on Climate Change details specific targets for renewables. This tallies with GEM data showing no renewables in development.

Appendices

Summary data tables for CCA countries, by source and development status. Construction projects include those where site preparation and equipment installation are underway. Pre-construction projects are those that are actively moving forward in seeking governmental approvals, land rights, or financing. Announced projects include those described in corporate or government plans or media releases but have not yet taken concrete steps such as applying for permits. Retired projects describe those decommissioned or dismantled; this term is also used if the plant has been destroyed by war.

About the Global Integrated Power Tracker

The Global Integrated Power Tracker (GIPT) is a free-to-use Creative Commons database of over 116,000 power units globally, that draws from GEM trackers for coal, gas, oil, hydropower, utility-scale solar, wind, nuclear, bioenergy, and geothermal, as well as energy ownership. Footnoted wiki pages accompany all power facilities included in the GIPT, updated biannually. For more information on the data collection process that underpins GEM’s power sector trackers, please refer to the Global Integrated Power Tracker methodology page.