Key Points

- As of 2024, an estimated US$1.1 trillion of new liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminals are in development, up 6% from last year, despite repeated calls from the International Energy Agency (IEA) for the LNG trade to peak this decade in order to limit global warming to 1.5℃. There are 1,048.2 million tonnes per annum (mtpa) of LNG export capacity and 672.7 mtpa of LNG import capacity in development. New LNG projects that are under construction or are proposed risk becoming stranded assets in the energy transition.

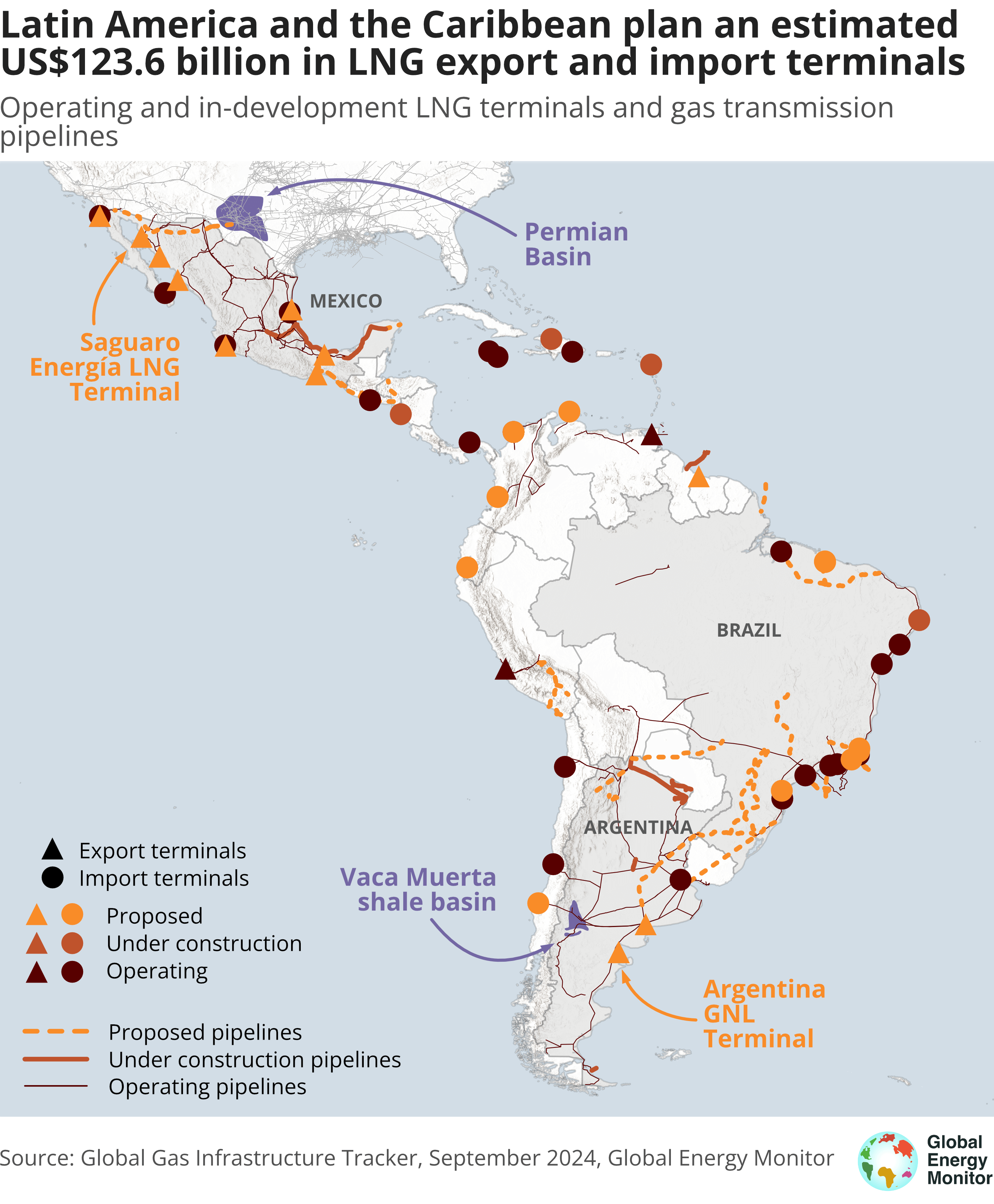

- Mexico and Argentina have proposed significant LNG export capacity additions that could make Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) a major exporting region, though these projects face barriers. Mexico’s proposed LNG export terminal buildout, which relies in large part on U.S. gas from the Permian Basin, is estimated to cost US$54.3 billion and is the third-largest slate of such projects in the world, with a total capacity of 73.6 mtpa. Argentina is planning one of the largest export facilities ever considered, the 30 mtpa Argentina GNL Terminal, which would draw on the Vaca Muerta shale basin and contribute to environmental injustices associated with its extraction.

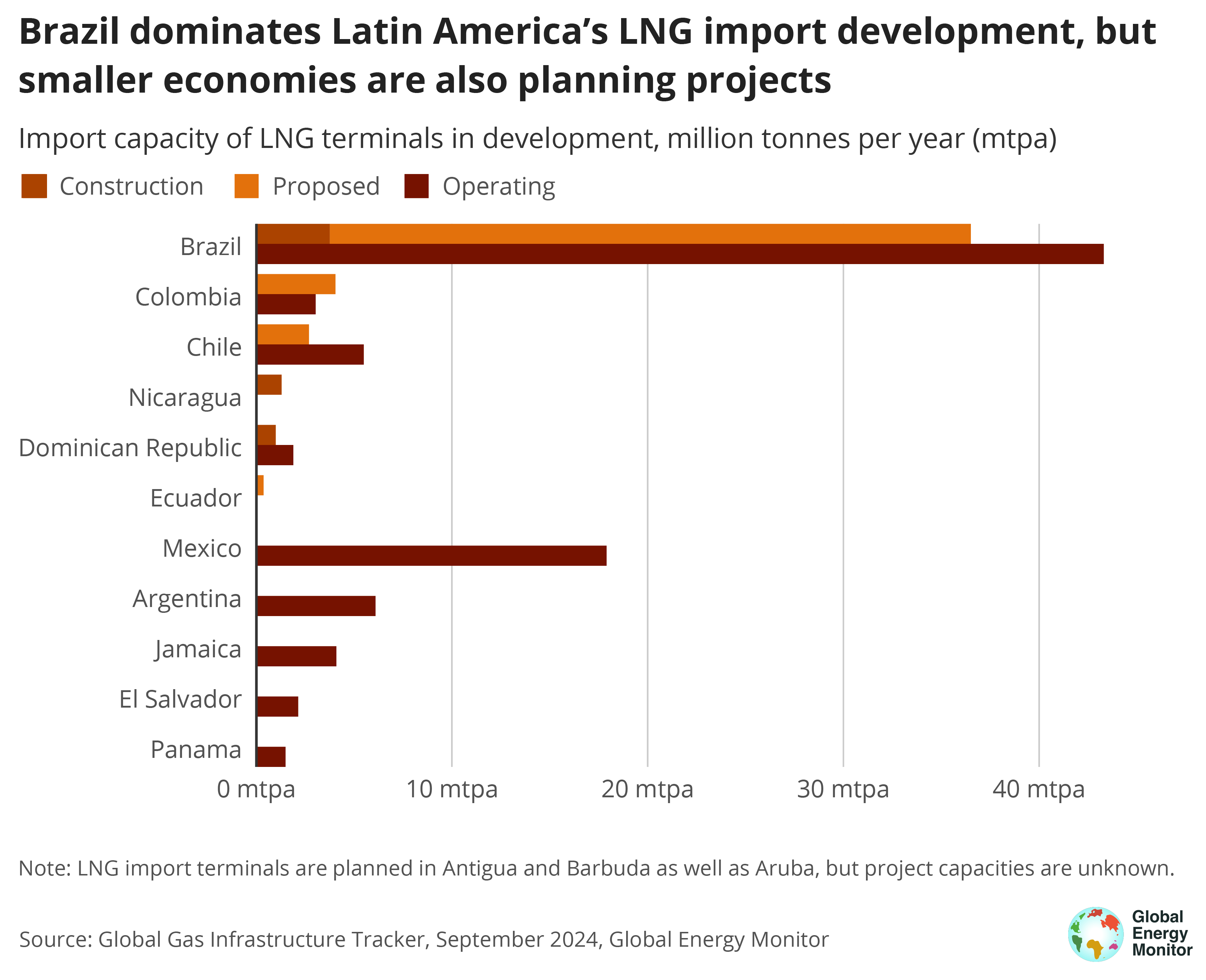

- LNG import terminals in development across the LAC region could cost US$7.2 billion and add up to 46 mtpa in new import capacity, which would boost existing capacity in the region by half. Brazil has the fourth-largest buildout of LNG import terminals in development globally at 36.5 mtpa.

- New LNG terminals also depend on or lead to the development of other massive gas infrastructure projects, such as pipelines and gas-fired power plants, which come with their own emissions, human health, and socio-ecological impacts. LNG terminals currently under development are connected to projects building 2,652 kilometers (km) in new gas transmission pipelines and 19.3 gigawatts (GW) in new gas-fired power capacity.

- New LNG import infrastructure risks locking the LAC region into further gas dependence for decades. Compared to increasing imports of foreign gas, countries’ ambitious renewable energy plans offer a more economically and environmentally sustainable path forward.

Introduction

In 2024, Latin America and the Caribbean’s plans for new LNG terminals assumed greater significance on the global stage — and continued to risk derailing the region’s energy transition. Planned LNG export and import terminals in the region total an estimated US$123.6 billion in new investments, much of which are concentrated in three countries: Mexico, Argentina, and Brazil.

In January, the U.S. government issued a pause on authorizing proposed LNG terminals to export U.S. gas to non-Free Trade Agreement (FTA) countries, a de facto permitting freeze on over a dozen U.S. projects, as the Department of Energy reevaluated whether such projects are in the public interest. While the policy’s future is now uncertain amid defeat in court and an upcoming election, the prospect of U.S. policy turning against new LNG exports has cast a spotlight on alternatives around the world. Mexico, in particular, has garnered attention as another outlet for U.S. gas to reach international markets, and its existing plans comprise the third-largest planned LNG export buildout in the world, totaling 73.6 mtpa (Figure 2). The majority of this capacity is not guaranteed to come online, especially given various permitting and financing barriers, but in 2024, Mexico launched its first LNG export terminal.

Meanwhile, Argentina advanced this year toward developing its first LNG export terminal, the massive 30 mtpa Argentina GNL Terminal, which would be one of the largest projects ever built. The terminal would export gas from the Vaca Muerta shale basin, which has long been an Argentinian national objective. The basin’s extraction has also been fraught with environ mental justice issues, and it has been described as a global “carbon bomb.”

At the same time, a fleet of import terminals proposed across the region, with half as much capacity in development as currently operating, could increase the region’s dependency on gas imports. In particular, Brazil has planned the fourth-largest buildout of LNG import terminals globally at 36.5 mtpa (Figure 2), and it brought online three new import projects just this year.

Many new LNG terminals would require or entail the construction of other gas infrastructure, such as pipelines and gas-fired power plants. These projects would involve even greater investments and come with their own emissions, human health, and socio-ecological impacts. According to GEM data, LNG terminals currently under development are connected to projects building 2,652 km in new gas transmission pipelines and 19.3 GW in new gas-fired power capacity. An additional 7.5 GW of gas-fired power capacity is under development to accept LNG from Brazilian import terminals that have come online since 2020. A list of these projects is shown in Appendix Table A5.

All of these expansions to the LAC region’s role in the LNG economy are being planned despite the IEA’s warning that the global LNG trade should peak in the middle of this decade for the world to meet its climate goal of limiting global warming to 1.5℃. New LNG export projects have a high likelihood of becoming stranded assets if countries meet their own climate objectives, and recent geopolitical events, including the war in Ukraine, have demonstrated the volatility and unreliability of LNG imports.

The LAC region’s LNG buildout faces significant barriers and is by no means certain to advance. Given the region’s abundant renewable resources and its progress planning new renewable energy projects, LAC could avoid sinking investment into the global LNG boom and focus on developing clean energy.

This briefing provides an overview of LNG development in the LAC region, focused on Mexico, Argentina, and Brazil, drawing on September 2024 data from Global Energy Monitor’s (GEM) Global Gas Infrastructure Tracker (GGIT). Data on multiple types of energy infrastructure across LAC can also be found in GEM’s Latin America Energy Portal.

Figure 1

LNG terminals by the numbers: 2024 GGIT update

Export terminals

467.9 mtpa operating capacity globally

2 mtpa became operational in 2024

31.9 mtpa set to be completed this year*

1,048.2 mtpa / US$969.8 billion in development, +14% from 2023†

281.3 mtpa shelved/cancelled since 2020

44% of capacity in development delayed

Import terminals

1,113.1 mtpa operating capacity globally

36.3 mtpa became operational in 2024

60.6 mtpa set to be completed this year*

672.7 mtpa / US$161.2 billion in development, -4.6% from 2023†

209.7 mtpa shelved/cancelled since 2020

26% of capacity in development delayed

*This figure includes in-construction projects that were not completed by GEM’s data update in September 2024 but are scheduled to come online by the end of the year.†Percent changes are in terms of capacity in development, with respect to GEM’s October 2023 GGIT data.

Figure 2

For more global LNG data, see the Appendix tables and GEM’s online resources for the GGIT including a tracker map, summary tables, dashboard, and data download.

Mexico’s LNG buildout would export U.S. gas, but projects face barriers

Mexico has the world’s third-largest set of LNG export projects planned, with 73.6 mtpa in export capacity proposed or in construction (Figures 2 and 3). The country’s sizable plans are notable in part because Mexico did not have any operating LNG export terminals until this year. In addition, the Biden Administration’s pause on LNG export authorizations has renewed attention on Mexico as an alternative pathway to export U.S. gas from the Permian Basin, although such projects are subject to the same U.S. policy.

In August 2024, Mexico’s first LNG export terminal began operations, the 1.4 mtpa Train 1 of New Fortress Altamira FLNG Terminal. In July 2024, owner New Fortress (NFE) reported that it had closed on a $700 million loan to finance Train 2, which is reportedly under construction and scheduled for commissioning in Q1 2026. NFE reports that it has a non-binding MOU with the Mexican government to construct up to three additional 1.4 mtpa trains, but details are sparse.

Just one other export facility is under construction in Mexico, Costa Azul LNG Terminal. Train 1 of this terminal (capacity 3.25 mtpa) is under construction and reportedly 85% complete as of August 2024. Until recently, commercial operations were expected in 2025, but labor and productivity challenges have now pushed commissioning back to Q1 2026, close to the U.S. Department of Energy’s March 29, 2026 “export commencement” deadline. The much larger Train 2 (12 mtpa) is still “under development,” according to Sempra’s most recent quarterly report (August 2024).

Mexico’s most ambitious proposal is Saguaro Energía LNG Terminal, which comprises three to six trains with a total capacity of 15–30 mtpa, making it among the largest projects under consideration globally (Table 1). Owner Mexico Pacific Ltd (MPL) has already signed nine contracts with seven Asian-Pacific customers to supply 14.1 mtpa of LNG over the next 20 years. However, the company has repeatedly delayed a final investment decision (FID), most recently until 2025. The terminal’s gas supply will be contingent on construction of the 250-km Saguaro Connector Pipeline in the U.S. and the 800-km Sierra Madre Gas Pipeline in Mexico, with anticipated start-up dates no earlier than 2027 and 2028, respectively. Mexico Pacific’s current export agreement with the U.S. Department of Energy expires in December 2025, meaning that an extension will be necessary to get the project off the ground.

Broadly, Mexico’s LNG buildout faces barriers that could significantly limit how much new capacity will be built. Complicated permitting processes with long wait times have challenged developers, in large part due to the Mexican government reducing permitting staff and prioritizing public over private permits, but also exacerbated by the U.S. LNG pause. New pipelines are required for several projects, including — as mentioned above — the Saguaro Energía terminal, and its proposed Saguaro Connector Pipeline (Appendix Table A5), which is facing legal challenges brought by consumer and environmental advocates. There are also concerns in Mexico about securing enough gas for domestic use. Mexico relies on the U.S. for most of its gas supply, and there is a risk that the U.S. could curtail piped gas to Mexico, as it did during a 2021 winter storm, or as it might do under the policies of an “America First” Trump presidency. BNamericas has reported that, amid these issues, “financiers are getting cold feet and developers are delaying final investment decisions.” Columbia’s Center on Global Energy Policy has said, “Most of these [Mexican LNG] projects are unlikely to be built due to financial constraints, among other challenges.”

Like LNG projects on the U.S. Gulf Coast, many proposed Mexican LNG projects pose environmental and environmental justice threats. These export terminals could harm low-income and marginalized communities in Mexico already suffering from industrial pollution, and many projects have not obtained a social license from local communities or Indigenous peoples. Shortly after the U.S. LNG pause, Greenpeace Mexico and others petitioned the Mexican government to follow suit and block its projects given their health, environmental, and climate impacts. The organization has also called attention to the impacts of Mexico’s biggest planned project, Saguaro Energía LNG Terminal, on whales and other marine life in the Gulf of California. Just as Mexico’s projects are an extension of the U.S. LNG buildout, they risk exporting the harm of U.S. fossil fuel activities into the communities and environments of Mexico.

Figure 3

Argentina’s LNG megaproject would enable extraction of the Vaca Muerta

Argentina has the world’s eighth-largest planned buildout of new LNG export capacity (Figure 3), primarily due to the US$30 billion Argentina GNL Terminal proposed by Argentina’s YPF and Malaysia’s Petronas (although the latter recently indicated it may exit the project). In August of this year, the project advanced as its sponsors reached agreement on siting the new LNG export terminal at Punta Colorada, near the municipality of Sierra Grande in Río Negro province, with a FID expected in 2025. If developed as planned, the Argentina GNL megaproject would involve construction of three new pipelines and a terminal built in three phases to a total capacity of up to 30 mtpa, easily the largest LNG export project in the LAC region and among the largest in development globally (Table 1).1

The Argentina GNL Terminal would export gas from the Vaca Muerta formation in Neuquén province, the world’s second-largest shale gas deposit. Exploiting this resource has been a longtime national objective. Production at Vaca Muerta started more than a decade ago, but gas distribution was limited by insufficient transmission infrastructure, forcing Argentina to rely on seasonal LNG imports during the winter months through the Bahía Blanca GasPort FSRU and Escobar FSRU import terminals. In July 2023, everything changed with the commissioning of the 573-km, 21 million cubic meters per day Néstor Kirchner Gas Pipeline, which has relieved bottlenecks and set off a chain reaction of new pipeline construction designed to bring Vaca Muerta gas to Buenos Aires and beyond.

Fracking and exporting gas from the Vaca Muerta shale basin is controversial because of environmental justice and climate impacts. Indigenous communities have seen their territories licensed for new developments despite opposition. Communities in the vicinity of fossil fuel activities have “faced a lack of access to potable water; increases in health problems […]; and pervasive toxic remnants of extraction in the form of open-air pits and landfills,” and extraction work threatens the livelihoods of locals such as farmers. A significant share of the profits from the gas field development go to foreign companies, and projects have not brought benefits to local people as promised by the authorities. The impacts of extraction activities on people and environments also extend well beyond the shale basin, with existing and planned fossil fuel projects, such as pipelines, sprawling across Argentina and into neighboring countries. Finally, the resource has also been described by environmentalists as a “carbon bomb,” one that could eat up 11% of the world’s carbon budget to limit warming to 1.5℃.

Table 1

A few smaller LNG export projects are being pursued in Argentina as well. In July 2024, Golar and Pan American Energy announced that they had signed a 20-year agreement for the Golar-Pan American FLNG Terminal with a capacity of 2.45 mtpa and a 2027 start-up date. In the same month, Argentine gas pipeline operator TGS confirmed that it was also studying the possible development of a 4–5.3 mtpa LNG export terminal, TGS Puerto Galván LNG Terminal, at Puerto Galván in Bahía Blanca, Buenos Aires province.

Figure 4

Brazil plans one of the world’s largest LNG import expansions

Brazil is the largest LNG importer in the LAC region, and it has planned the world’s fourth-largest buildout of LNG import capacity, totaling 36.5 mtpa (Figures 2 and 4). The country relies on imports for approximately 40% of its gas supply. Historically, most imported gas came from Bolivia, but production declines have prompted Brazil to consider fracked gas from Argentina and imported LNG as alternatives. Additionally, while hydropower can provide most of Brazil’s electricity, unreliable generation during droughts in recent years has pushed Brazil toward developing LNG import capacity.

Prior to 2020, Brazil only had three LNG terminals — Pecém FSRU, Guanabara Bay FSRU, and Bahia FSRU — with a total import capacity of 17.5 mtpa. However, the country’s LNG import capacity has more than doubled over the past five years (Figure 5). Two new import terminals, New Fortress Barcarena FSRU and Terminal Gás Sul FSRU (each with a capacity of 6 mtpa), began commercial operations in the first quarter of 2024, joining a wave that began in 2020 and 2021 with the commissioning of the Sergipe FSRU and Porto do Açu FSRU terminals (5.6 mtpa each) and the 2.7 mtpa Sepetiba Bay FSRU in 2022. Two other new terminals (Cosan FSRU and Suape FSRU) will come online in 2024 or 2025.

Figure 5

The surge of new LNG terminals has coincided with development of several large new gas plants, including Porto de Sergipe power station (1.6 GW), GNA I power station (1.3 GW), GNA II power station (1.7 GW), and Novo Tempo Barcarena power station (2.2 GW). Several additional LNG import terminals remain on the drawing board, including the Tepor Macaé FSRU, Porto Norte Fluminense FSRU, Presidente Kennedy FSRU, Itaqui FSRU, Geramar FSRU, São Marcos Bay FSRU, Dislub Maranhão FSRU, and Nimofast Antonina LNG Terminal.

Other LAC countries plan one-fifth of region’s LNG import projects

Beyond Brazil, smaller economies in LAC are developing 9.4 mtpa in LNG import capacity, about one-fifth of such capacity planned across the region (Figure 4). In October 2023, the Chilean Council of Ministers revived the shelved 2.7 mtpa Penco Lirquén FSRU, granting it an environmental permit nine years after it was first proposed. The project is planned to start operating in 2027, though it faces legal challenges from local communities concerned about impacts on marine life. In Nicaragua, New Fortress is constructing the 1.3 mtpa Puerto Sandino FSRU, which is set to begin operations in Q4 2024, though it has suffered repeated delays, partly due to the threat of U.S. government sanctions against the country. Colombia has the second-most LNG import capacity in development regionally, 4.1 mtpa, though its projects such as the proposed Buenaventura FSRU have struggled to attract investors.

LAC has a safer path forward than LNG

Doubling down on LNG imports could be a risky path forward for LAC countries. Recent geopolitical events, notably the war in Ukraine, have demonstrated the volatility of the global gas market — in 2022, gas prices were 40% higher in Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay. Latin America and the Caribbean also felt the impacts of this energy shock through the price of fertilizer, tightly linked to the cost of gas, which was almost 190% higher in the first half of 2022 compared to that period of the prior year.

Moreover, there is a risk that investments in new LNG terminals across the region — totaling an estimated US$123.6 billion — could be underutilized in the energy transition and ultimately waste public and private resources. The IEA, in its conservative Stated Policies Scenario (STEPS), has said that most new electricity generation in the region will be provided by solar and wind power and noted that if domestic gas production increases, it could limit the use of gas import infrastructure. The organization has also noted that, under various scenarios, LNG exporters in the LAC region “face the risk that new projects are not cost-competitive or result in stranded assets.” As recently as the start of this year, Energy Intelligence forecasted that South American LNG imports were expected to be down in 2024, “as a gloomy economic outlook and renewable power sources are expected to eat into natural gas demand looking forward.”

LAC has a safer path forward: fast-tracking its energy transition and focusing investments on clean power, while avoiding fossil fuel market volatility and stranded asset risks. Renewable energy sources, including mega-hydropower projects, already provide 60% of the region’s electricity, and even as hydropower has faltered in Brazil this year due to drought, generation has been primarily replaced by solar and wind. In the 2023 Race to the Top report on solar and wind development in Latin America and the Caribbean, GEM found that the region is “on track to meet, and potentially surpass, [IEA] 2030 regional net zero renewable energy goals if it implements all of its prospective larger-scale projects.”

Conclusion

New LNG infrastructure in Latin America and the Caribbean could alter the region’s energy sector and its role in global gas markets, though a large LNG buildout is by no means certain. On the export side, massive investments in new terminals are a great risk in the energy transition. And on the import side, renewable energy paired with storage represents a more sustainable path forward. With abundant solar and wind resources and a strong slate of renewable projects already in development, the LAC region is well-positioned to sidestep the global LNG boom and build quickly toward a clean energy future.

1 The Argentina GNL Terminal project is the third-largest LNG export terminal in development anywhere around the world if developed to its maximum proposed capacity of 30.2 mtpa (Table 1), and it would be the biggest investment in Argentine history.